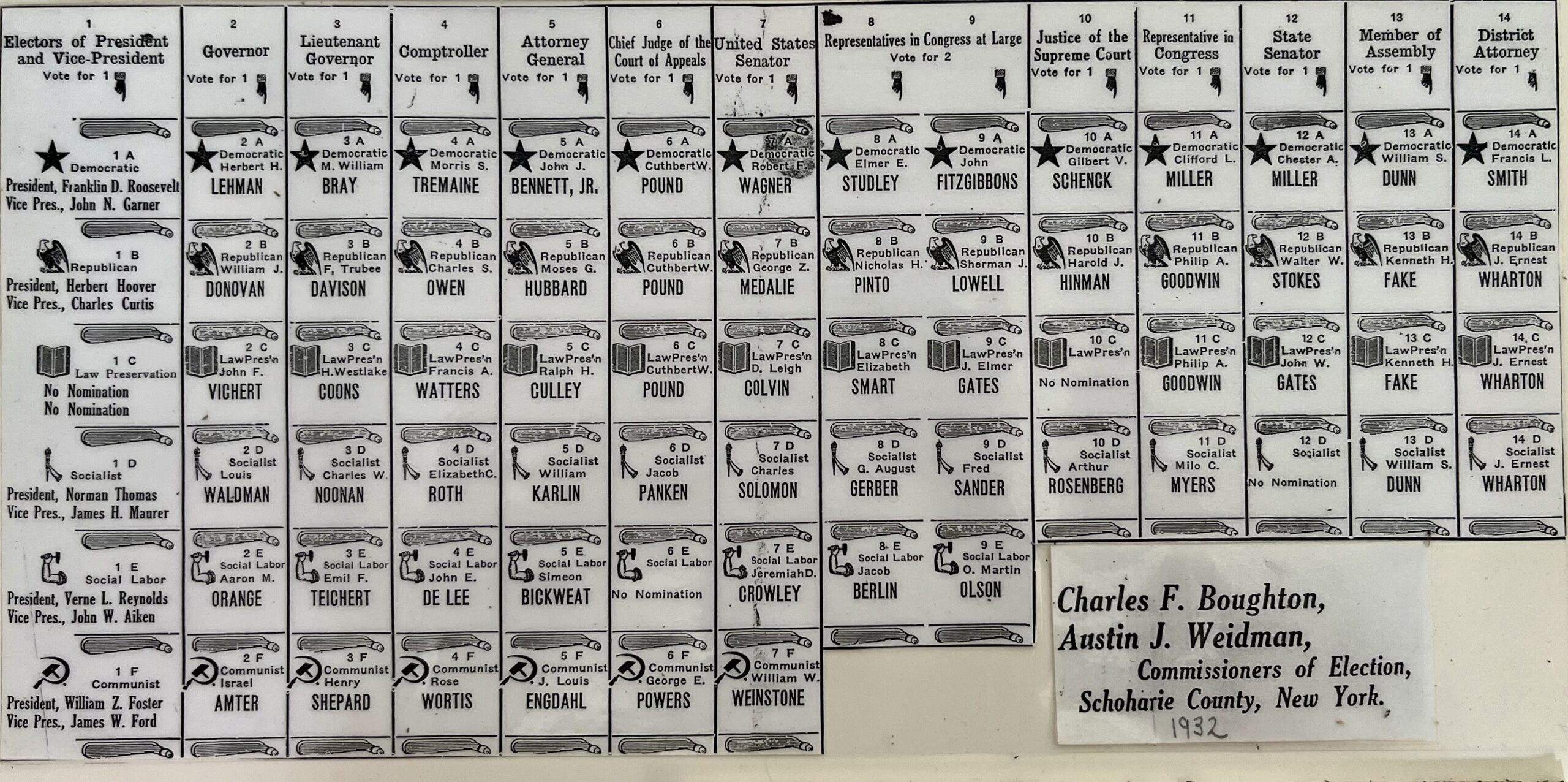

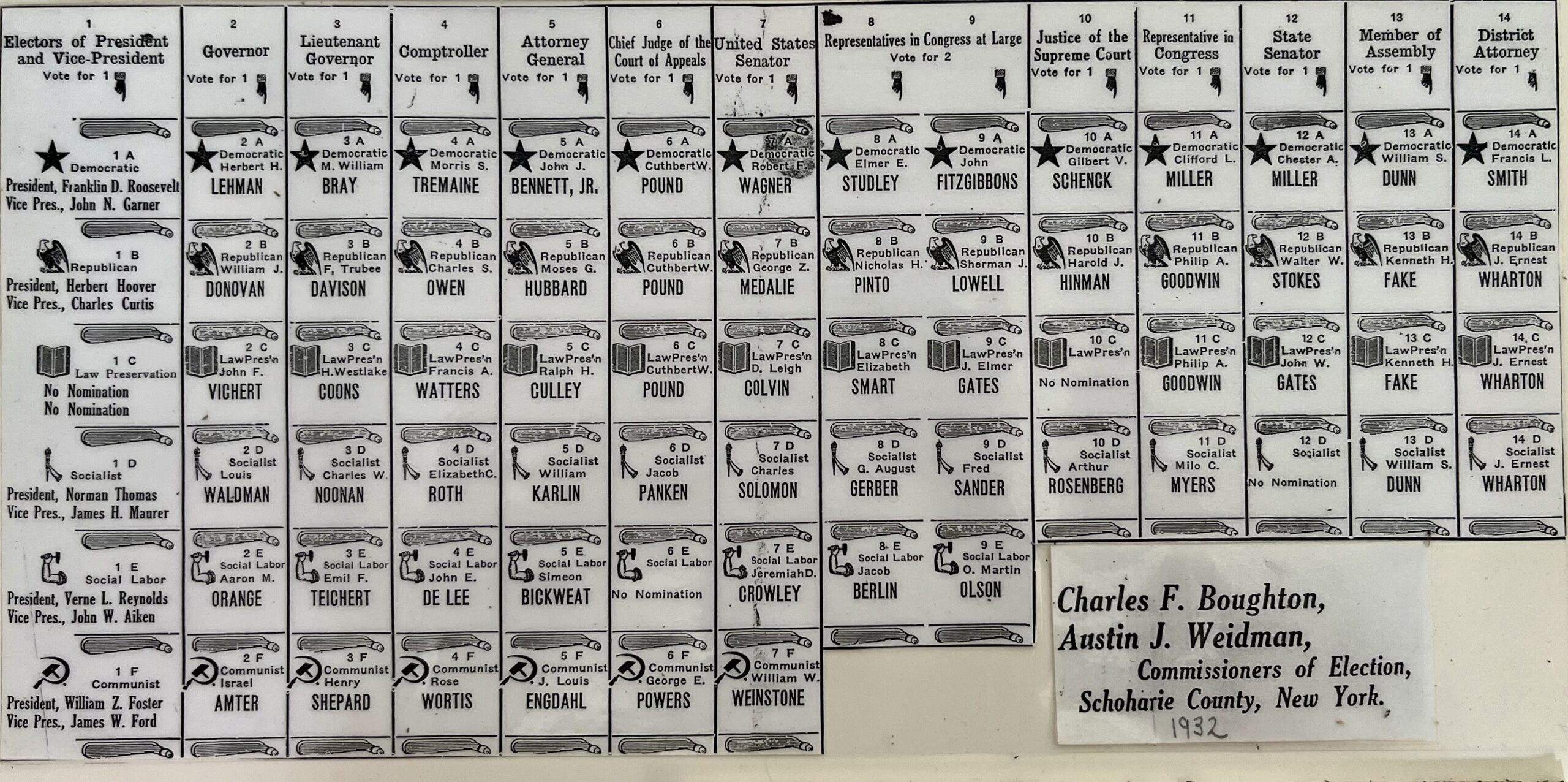

Tucked inside The Jackson Law Office by the old voting machines at The Stone Fort Museum’s Early Law and Government exhibit is a replica of the 1932 U.S. presidential ballot. The story of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s victory over incumbent Herbert Hoover is well documented. However, with a few scratches at the surface, one can unveil histories that are not as widely told yet are just as critical. Modern voters might be taken aback to see the Communist Party U.S.A. (CPUSA) on the ballot. The CPUSA first appeared on the ballot in 1924 and had been a public organization for nearly a decade after emerging from the underground in 1923.1 However, with Herbert Hoover’s ill-fated refusal to respond to Capitalism’s failure, many suffering Americans became open to alternatives, and interest in Marxist groups, or at the very least their platforms, was growing as voter turnout for the CPUSA would reveal. Yet another episode, brought on by the economic crisis, would drive voters away from Hoover in November, that of the often-overlooked Bonus Army. Between May and July of 1932, approximately 20,000 World War I veterans and their families marched on Washington to petition the government for their adjusted compensation bonus.2 The payment was not due until 1945, but for many vets and their families, their bonus certificates were the only thing of monetary value they had left, and they needed the relief sooner. The CPUSA had also begun to call for the bonus in 1932. The Bonus Army and a small group of Communists separately descended on Washington, leading to an unprecedented, violent showdown that further tarnished Hoover’s reputation as the nation began to see the plight of the Bonus Army as their own and the platform of the Communists as increasingly appealing. The Communist Party in the U.S. had been in decline by the 1930s. Party membership decreased from 9,300 in 1929 to 7,545 in 1930 despite recruiting 6,000 new members, meaning the party had hemorrhaged some of its older members.3 Much of this was due to factionalism within the CPUSA, with high-profile members facing expulsion over various disagreements and orders from the Communist International (Comintern), which ultimately answered to the Soviet Union. Born from a split within the Socialist Party in 1919, the Communists had existed underground during what they called “The First Period,” brought on by the Bolshevik Revolution. They emerged from the underground in 1923 during the so-called “Second Period,” denoted by “capitalist stabilization.”4 In 1928, the Comintern announced the beginning of “The Third Period,” an era that they believed would be marked by “capitalist decay” and the arrival of a proletariat revolution.5 The Comintern’s predicted “crisis of capitalism” was decidedly more accurate than Hoover’s optimistic speech of that same year. “We in America today are nearer to the final triumph over poverty than ever before in the history of any land,” declared Hoover as he accepted the Republican presidential nomination on August 11th, 1928.6 Hoover was in office just seven months before the stock market would crash on Black Tuesday, October 24th, 1929, tipping off the Great Depression. However, it was not that the Communists were reading tea leaves that Hoover could not see; Karl Marx had been predicting the imminent collapse of Capitalism since the mid-19th century, and the Comintern’s prognostication was more likely an extension of Marx than any acute economic savvy. 7

The Great Depression, then, seemed like the moment they’d been waiting for. “If there was ever an experiment designed to test the Communist party,” wrote historian Harvey Klehr, “This was it.”8 The CPUSA was oddly slow to respond, but by 1931, they had effectively honed their approach to the crisis, forming unions, leading strikes, demanding unemployment benefits, and an 8-hour work day. The CPUSA also sharpened its focus on issues of racism in the Third Period, becoming the “first largely white U.S. radical group to focus attention on the plight of blacks.”9 The CPUSA notably organized legal defense for the Scottsboro Boys, and with the nomination of James W. Ford as their vice-presidential candidate in 1932, became the first party to include an African-American on a presidential ticket. Ford traveled to Washington in April 1932 to speak before Congress, demanding a total cash payment of the bonus and unemployment insurance.10 Just four months earlier, at the Communist-led and organized National Hunger March in Washington, four hundred vets, members of the Workers Ex-Servicemen’s League (W.E.S.L., or ‘weasel’ to its critics) caucused and agreed to fight for the bonus.11

Calls for the bonus were not new, but the conversation had changed. In 1924, over President Calvin Coolidge’s veto, Congress passed a law promising veterans of the Great War an adjusted universal compensation, colloquially known as the bonus.12 The law would grant servicemen a dollar per day for any domestic service and an added twenty-five cents per day for time spent overseas redeemable in 1945.13 Vets nicknamed it The Tombstone Bonus, as many believed they would die before receiving the payment; some even thought they had to die to receive it.14 None of this sat well with Wright Patman. Patman, a Texan Democrat, veteran, and newly elected Congressman, began calling for “an immediate cash payment of the bonus” in May 1929 and co-sponsored a bill that ultimately died on the committee floor.15 Patman reintroduced the bill in February 1932.16

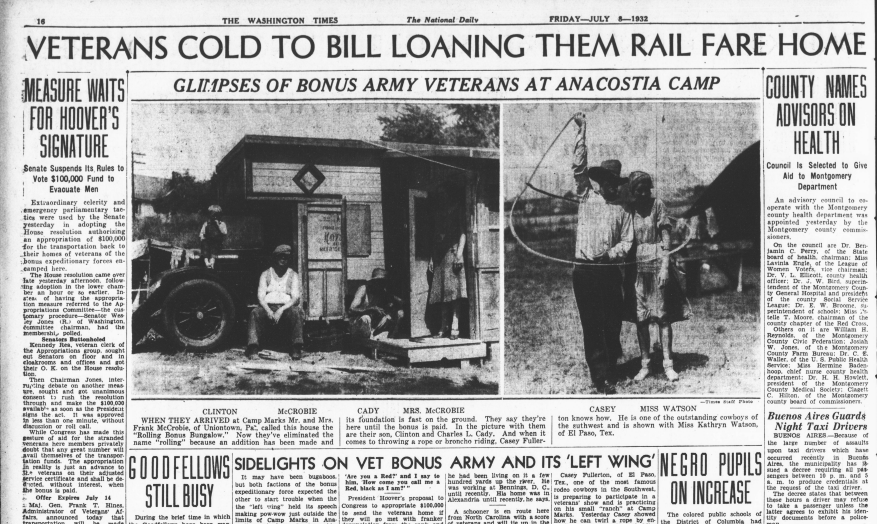

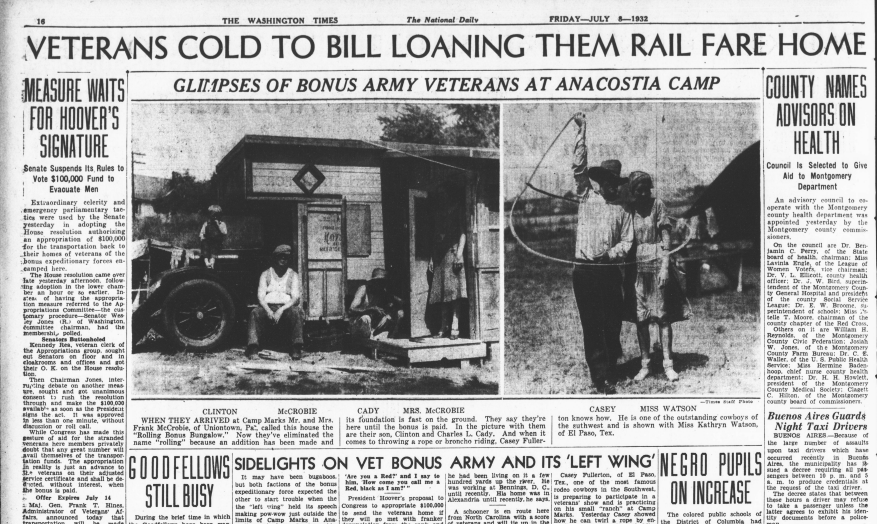

Walter Waters was a veteran of the First World War living in Portland, Oregon. He and his wife Wilma were broke and nearly possessionless in March 1932. “…our personal belongings, one by one, found their way to the pawn shops,” he wrote in his 1933 memoir. “There were many days that winter we experienced actual hunger…”17 Waters had served in WWI and was among the troops who remained on the firing lines on November 11th, 1918, waiting for the 11th hour to signal the silencing of the guns. Like many struggling vets, Waters kept a keen eye on reports regarding the bonus, hoping for good news. But no such news arrived, and on May 11th, 1932, Waters and a group of roughly three hundred out-of-work veterans left Portland, Oregon, with just thirty dollars between them on a cross-country trek to Washington DC to petition Congress for their bonus with a banner reading “Veterans Bonus March- On To Washington.” “All we can hope to do is make them statesmen in Washington vote on the Bonus and go on record,” explained one member. “Then we can lick the guys that voted against it in November.”18 The marchers dubbed themselves The Bonus Expeditionary Force, or B.E.F. The B.E.F. made their way across the country, riding railcars, hitchhiking, and walking, with Waters insisting on upstanding behavior to not undermine their goal. Waters’ account of the journey reads like a Steinbeck novel, with the bedraggled vets hopping empty cattle cars and outsmarting the railroads en route to their destination.19 Newspaper reports of their exploits began to attract the attention of other vets desperate for their bonuses. By May 28th, thousands had arrived from all over the country. A small group of Communists from W.E.S.L., led by John Pace, also descended upon the city.

Greeting the vets as they arrived was newly elected district police commissioner Pelham Glassford. Glassford had served in the war and had already demonstrated a gentle-handed approach to protesters. He oversaw the National Hunger March from his motorcycle, practicing his policy of “forceful courtesy,” and kept the peace while the federal government placed soldiers unnecessarily on “wartime guard.”20 From the arrival of the B.E.F. in May to their ultimate removal on July 28th, Glassford’s “forceful courtesy” approach maintained order, eased tensions, and even alleviated suffering. Glassford often reached into his own pockets to ensure the vets had food and worked to deliver cots to the eventual campground at Anacostia Flats, an area just outside of the city across the Anacostia River accessible only by a drawbridge.21 Therein lies the gist of Glassford’s strategy; the district would work with the vets, but if there were signs of trouble, Glassford could raise the drawbridge and isolate the demonstrators. John Pace’s Communists set up camp in an abandoned building within the city. Shockingly to Glassford, the B.E.F., and eventually to the rest of America, it was not the downtrodden vets or the Communists who would resort to violence in the nation’s capital but the U.S. military under the command of General Douglas MacArthur that would eventually unleash terror.

Early on, Herbert Hoover and Douglas MacArthur insisted that the protestors were not vets but radicals and criminals looking to foment revolution, alleging the camps at Anacostia were littered with Communists. In reality, the small group of Communists in D.C. led by John Pace never exceeded 200, and they were aggressively unwelcome in the Bonus Army camps. Glassford had set them up in a separate vacant building at 13th and B Streets.22 Waters and the Bonus Marchers were openly anti-communist (Waters eventually openly dabbled with fascism) and felt the “Reds” could undermine how Congress and the American public perceived them. Waters admitted there were “some veterans among them we shared,” but that was where the relationship halted.23 “My chief problem with the Communists was to prevent the men of the B.E.F., literally, from almost killing any Communist they found among them,” wrote Waters.24 Waters strictly enforced a “veterans-only” rule and enlisted M.P.s to “heave out real or suspected Communists.”25 In turn, the Communists saw no ally in Waters, referring to him as a “petty bourgeois demagogue.”26 The CPUSA believed they had come up with the idea for the Bonus March and very likely did, but it had grown into something outside of their control.27 The Bonus Army embodied nearly everything the Communists could hope for in a mass movement—an organized group of aggrieved unemployed making radical demands of the government. And make no mistake about it, The Bonus marchers were radical in their approach and what they were calling for, but they were not radical in the sense that they wanted to overthrow the U.S. government, which is precisely what the CPUSA did want in order to establish a worldwide Soviet. Even more remarkable, the camps at Anacostia were entirely desegregated. Vets who had fought in a segregated army encamped in a Jim Crow-segregated Washington united together (at least visibly) around their cause. The CPUSA would claim credit for the desegregation in a September issue of The Communist.28 However, all other accounts indicate they would have had no such influence on the Bonus Army. If the CPUSA could not infiltrate the Bonus March, they could at least propagandize it as they had in the September issue of The Communist and would continue to do so throughout leading up to the election.

Despite Waters’ vehement anti-communist stance and reports from Glassford that the Communists were not running the demonstration, MacArthur maintained his belief that an insurrection was brewing. MacArthur likely hoped there was a Communist revolution brewing so he could put into action the “White Plan,” an untested militarized response to a potential civilian uprising created in the early 1920s after the Bolshevik Revolution.29 Unbeknownst to the Bonus marchers, MacArthur had the army rehearsing the White Plan at a nearby Fort Meyer.30 As Congress adjourned with no Bonus Bill enacted, many expected the protestors to leave, and some did, accepting stipends to depart. But many had no homes to return to and remained in the city, and as the Bonus Army dug in, tensions began to rise in the sweltering Washington DC summer.

The presence of the Bonus Army was an embarrassment for Hoover. Fueled by MacArthur’s insistence that radicals, Reds, and criminals populated the camps, he had taken to isolating himself in the White House, a man in his lonely tower. In late July, Glassford received orders to begin evacuating the encampments. Glassford had negotiated on behalf of the marchers to let some men occupy abandoned buildings set for demolition along Pennsylvania Avenue (the men had dubbed one of the buildings Camp Glassford).31 Now, his superiors were ordering him to evacuate the buildings. Glassford maintained his gentle hand in the matter, making every effort to keep things peaceful, and by noon, Camp Glassford had been evacuated without issue.32 Feeling betrayed, Waters ordered those camped at Anacostia to Pennsylvania Avenue to interfere with any more attempts at evictions. John Pace and the Communists rushed to the scene as well from their camp. Men were angry and felt betrayed at the sight of Glassford involved in the evictions and began to throw bricks and stones at the police. One man ripped Glassford’s badge from his shirt.33 Miraculously, Glassford was able to restore the calm. But after the outburst, calls to summon MacArthur had grown louder.

Sometime after noon, two vets began quarreling inside one of the abandoned buildings. Police officers rushed in to intervene, but the officers were jeered and followed by onlookers who disagreed with their involvement, and some began throwing punches. In the panic and feeling cornered, an officer began to fire, hitting and killing vet William Hushka and mortally wounding fellow vet Eric Carlson. Again, Glassford intervened and restored the calm, but the situation had tragically crossed the Rubicon. Given the chance, Glassford might have orchestrated a slow but peaceful removal of the Bonus Marcher by summer’s end. Unfortunately, he would have no such opportunity. The district commissioners delivered a falsified report to Hoover purporting to have come from Glassford requesting that Hoover send the military to clear the camps, citing the presence of criminals and radicals (Glassford had made no such request).34 MacArthur wanted Hoover to declare martial law, which the president declined, insisting the army only assist the police in clearing the camps. MacArthur, as history would continue to prove, behaved as if he had absolute authority, disregarded the orders, and unleashed holy hell on the veterans he had served alongside in the Great War.

With a young Dwight D. Eisenhower as his aide de camp and General George S. Patton, MacArthur led a group of soldiers too young to have witnessed the horrors of the Western Front toward the tired, homeless men who had served and their families. MacArthur proudly paraded tanks and cavalry down Pennsylvania Avenue. Some vets even assumed it was a parade, possibly in their honor, but when the tear gas began filling the air and bayonets began poking their sides, they knew it was no veteran’s parade. Defying orders and enacting his White Plan against unarmed demonstrators, MacArthur, and the army had the city limits cleared by 6:45 P.M. Most had fled toward the camps at Anacostia. John Pace and the Communist contingent had cleared out entirely. MacArthur received orders from Hoover not to pursue the marchers across the drawbridge to Anacostia. Again, the smug General could not be bothered with orders from his president. As MacArthur stopped for dinner, Glassford alerted the remaining groups across the drawbridge of what was coming. At 10:00 P.M., ignoring Hoover’s orders, MacArthur ordered the troops across the bridge and oversaw the mayhem as they systematically burned the shacks and intimidated the vets, women, and children remaining to drive them out. A twelve-week-old baby, Bernard Meyer, perished from health complications due to inhalation of the tear gas.35 By morning, Anacostia was a smoldering pile of rubble under the shadow of the U.S. Capitol. News traveled to Franklin D. Roosevelt in Hyde Park, who wondered, “Why didn’t Hoover offer the men coffee and sandwiches instead of turning Doug MacArthur loose?”36 But the president-to-be was also savvy enough to see the moment for what it was. “Well, Felix,” he said to his confidant Felix Frankfurter, “This will elect me.”37

Hoover was livid with MacArthur. In a private meeting the following morning, Hoover chastised the General for ignoring his orders.38 From his office in the Lincoln Study, he could see the red flames licking the night sky from the burning shacks at Anacostia.39 Publicly, however, Hoover fell into lockstep with MacArthur’s narrative and issued a statement claiming “a large part” of the veteran’s groups were not veterans at all but criminals and Communists, setting the tone for the White House’s official stance on the matter.40 Not only would it set the tone for the White House’s justification of violence against its own war veterans, but it signaled a defining characteristic of the United States’ domestic and foreign policies for nearly all of the remaining 20th century. With Communism as the convenient bogeyman, the U.S. would send young men to foreign wars, sabotage anti-war and civil rights groups, and even resort to murdering U.S. citizens in the name of defending the country against the Communists. Herbert Hoover would go to his grave convinced that the Bonus Army had been a Communist demonstration and not one containing Great War veterans, viewing himself as a “victim of fate.”41 But how much of a threat were the Communists at home? The CPUSA received 103,307 votes in the 1932 presidential election, the highest it would ever receive, and its membership increased from roughly 7,000 in 1929 to 26,000 in 1933.42 The CPUSA’s popularity plateaued in the early days of The Great Depression, drawing new members and “fellow travelers” desperate for the assistance the Communists were promoting before their numbers eventually tapered off again when most found their tactics off-putting. Yet their influence on the outcome of the 1932 election cannot be overlooked.

On the one hand, the Communists’ involvement with the Bonus Army increased Hoover and MacArthur’s paranoia to the point where their actions all but handed Roosevelt the presidency. On the other, Roosevelt eventually adopted many of the causes promoted by the CPUSA in his New Deal policies, including unemployment insurance and an 8-hour work day (in the form of a 40-hour work week). In this sense, the CPUSA’s influence on the election was two-fold. When combined with the turnout for the Socialist Party and the Socialist Labor parties in November, voters cast over one million for parties derived from Marxist philosophies. Third party candidates, in this sense, can experiment with “fringe” platforms, and if they seem to resonate with the electorate, major parties feel more comfortable adopting them into their own. For example, the cancelation of student debt was not a significant component of the Democratic Party platform until Senator Bernie Sanders’s run for office in 2016 galvanized support for the idea, which the Biden administration has since adopted. Similarly, the Communist platform influenced Roosevelt’s New Deal policy, ironically diminishing the CPUSA’s appeal. With Roosevelt answering the call to those in need, what need did they have for radical Communists and their devotion to the Soviet Union? Under Hoover, The CPUSA emerged as an organization responding to the desperation brought about by The Great Depression and, to many, seemed like the only ones hearing their pleas. Under Roosevelt, this was predominantly not the case.

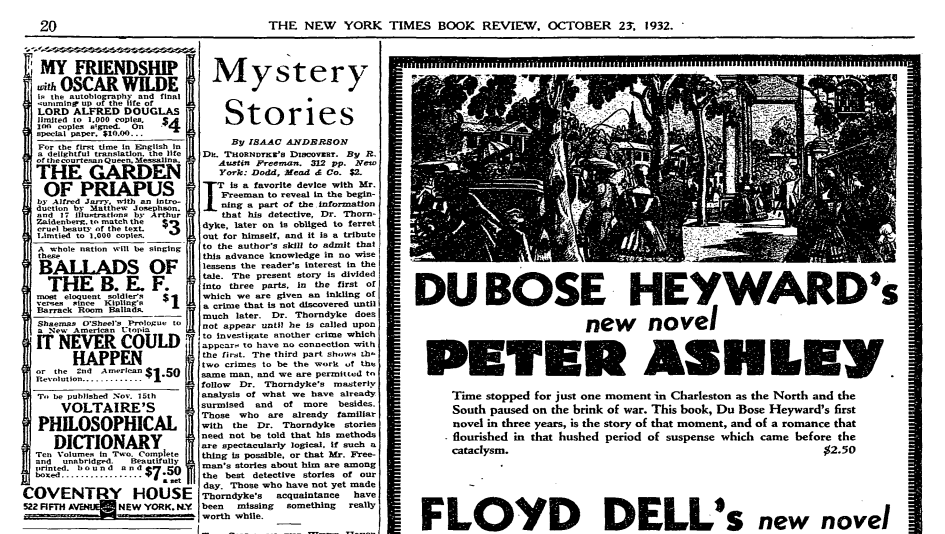

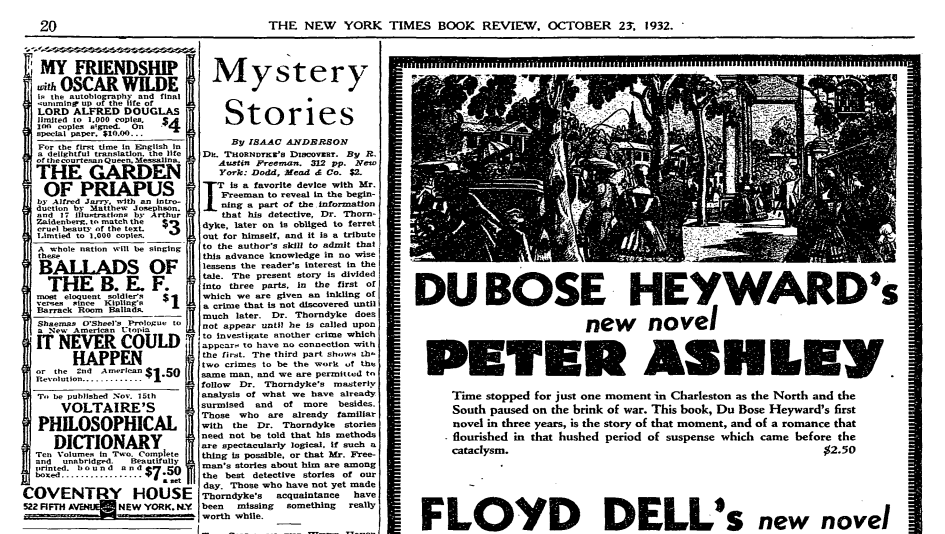

The CPUSA would continue to propagandize the events and exaggerate their role in the Bonus Army leading up to the November election. And why wouldn’t they? They believed they had inspired it (and likely had to some extent), and the Hoover administration blamed them. It was an ideal, high-profile moment for them to seize, and seize it they did. “The Communist Party throughout the struggle acted as the organizer and leader of the masses of veterans in their struggle for the bonus,” they claimed in the September issue of The Communist.43 In October, the CPUSA published a book of “songs” entitled Ballads of The B.E.F. Each “song” is a parody of a known melody, rewritten with topical lyrics, a common technique used by the Wobblies and picked up by the Communists.44 “A whole nation will be singing these Ballads of the B.E.F.,” proclaimed an ad in the New York Times, calling it the “most eloquent soldier’s verses since Kipling’s Barrack Room Ballads.”45 Promoted in the same ad was Shaemus O’Sheel’s “Prologue to a new Utopia” It Never Could Happen or the 2nd American Revolution, a fictionalized account of the Bonus Army episode. Ballads of the B.E.F., a digitized version of which accompanies this article (click here), depicts not only the Communists’ savvy of tapping into the most sympathetic aspects of the Bonus Army, like the deaths of Carlson, Huska, and Meyers, but also a sharp critique of Hoover, juxtaposing his reputation as “The Great Humanitarian” for his relief efforts in Belgium following the Great War with his callous treatment of the Bonus Army.46

Veterans’ groups and Wright Patman would continue to push for the immediate payout of the bonus. Smaller marches petitioning for the bill would occasionally come to Washington, but none on the scale of the 1932 march. Eleanor Roosevelt once visited an encampment and listened to the vets’ tales. “Hoover sent the army. Roosevelt sent his wife,” quipped one vet as she left.47 Finally, in 1936, the First World War veterans received their bonus. Congress and the Senate approved a one-time cash bonus payout, overriding an unlikely opponent in the White House. Roosevelt, who had responded to so many of the needs of struggling Americans and even ultimately adopted some of the Communists’ platform in the New Deal, had vetoed the bill.