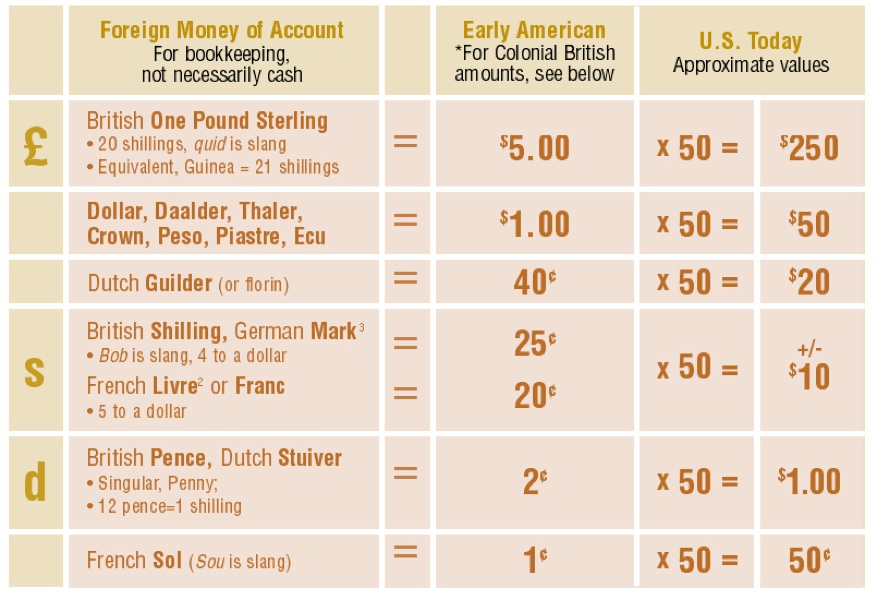

Historical money equivalents

Here’s how the Value Chart works.

-

There were about five Spanish or US dollars to a British pound of 20 shillings.‡ $5 is also 20 quarters! So a shilling and a quarter were about the same (also a Spanish-American 2-reales or a mark of Hamburg or Prussia).

-

French livres, francs and Spanish pistareens* were 5 to the dollar instead of 4. For easier math you can use their value, about 20¢, for all. .20 x 50 = $10.00 modern.

‡ Actually $4.44 until 1816, then $4.85, making a shilling about 22-24¢

-

*Pistareen: a Spanish-made 2-reales coin containing 20% less silver (known as new plate) than an American-minted coin. The name was sometimes used interchangeably with the genuine 2-reales in America.

-

*An Italian lira also equalled a franc after Napoleon. Before that estimate 6 lire to a dollar (±16¢.)

-

Don’t concern yourself about actual exchange rates for a given date or location. Leave that to the economic historians. Except...

Quarter-size silver coins, from left:

2-reales, shilling, early & modern quarters

The 2-reales is larger but thinner - about the same weight. (Note: a modern quarter is not silver.)

What was Money of Account?

There was a bewildering variety of coins circulating in Europe, minted by hundreds of empires, kingdoms, principalities, duchies, electorates, republics and free cities. Most were not so pure and stable as those listed above. Merchants and bankers kept their books in a few regional accounting systems, some units corresponding to actual coins, some to a weight of metal, others purely imaginary. For example, there was no British coin called a pound. Pounds were money of account, and coins worth one pound (non-existent until 1817) were called “sovereigns”.

It was relatively easy to do business in money of account using bills of exchange, similar to checks, and only convert to the current, local coin value when cash was needed. The value of a German reichsthaler of 24 groschen of account, for example, was always 3/4 of the current silver thaler (speciesthaler) value. So whether the local coin denomination was silbergroschen, kreutzer, mark, schilling, albus... a reichsthaler was worth 3/4 of however many of them equalled a speciesthaler.

The system transplanted to the colonies, where everyone in New York knew that their money of account, the York shilling, was worth half a British shilling, even though their coins were Spanish. Generally, when you’re reading history you’re reading money of account unless specie or coin is specified. "Lawful money" was money of account.