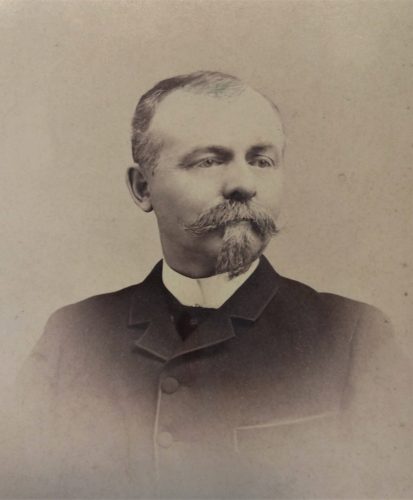

This Civil War Identity Disk (c. 1861) belonged to Captain Peter S. Clark, of Middleburgh, member of the 76th Regiment, New York State Volunteers, known as “The Cortland Regiment”.

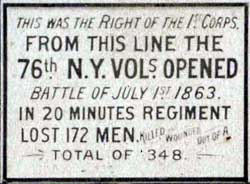

During its three years of existence, the 76th Regiment NY Volunteers fought with the Army of the Potomac in most of the battles in the eastern theater of the war, from Fredericksburg to Petersburg. At the Battle of Gettysburg, the 76th was “first on the field”, at the right flank of the entire army, and suffered terrible casualties as a result. The men of the regiment were mustered out or transferred to other regiments between July 1864 and January 1865, at which point the regiment ceased to exist.

According to the 1901 Adjutant General’s Report, Clark’s military record is as follows:

Age, 20 years. Enrolled, October 16, 1861, at Middleburg to serve three years; mustered in as sergeant, Co. I, October 28, 1861; promoted first sergeant, May 17, 1862; mustered in as second lieutenant, December 16,1862; wounded in action, July 1, 1863, at Gettysburg, Pa.; mustered in as first lieutenant, Co. G, to date March 31, 1863; as captain, October 23, 1863; discharged for disability, caused by wounds, November 9, 1863.

Commissioned second lieutenant, February 6, 1863, with rank from July 11, 1862, vice John Fisher promoted; first lieutenant July 31, 1863, with rank from February 22, 1863, vice C. A. Watkins promoted; captain, October 17, 1863, with rank from June 25, 1863, vice J. E. Cook promoted.

Peter Swart Clark was born to parents Napoleon Clark and Roxanna Clark (Netheway) in January of 1842. He was married to Annie M. Clark (Crounse) and was the father of Mary R. Clark Sternberg, Claude A. Clark, Charles Sherwood Clark and John Timothy Clark.

Captain Peter S. Clark died on April 28, 1928 in Gloversville, NY, at the age of 86. He is buried in a family plot at the Old Stone Fort Cemetery in Schoharie, NY. He joins more than 40 other Civil War soldiers interred at the cemetery. Many of the items Captain Clark carried with him throughout his service can be found on display at the Old Stone Fort Museum, including this identity disk, his Bible, sword and scabbard, brushes and his well-worn haversack.

About Civil War Identity Discs

Throughout the American Civil War, many soldiers faced the very real fear their bodies would not be identified if they lost their lives on the battlefield. Surprisingly, neither Union nor Confederate Armies supplied officially issued identification tags, what we could call “dog tags” today. In fact, in 1862, then U.S. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton staunchly rejected the idea with no explanation, leading many soldiers to employ their own techniques to ensure their identification, including simply pinning pieces of paper with their information written on them to their clothing or scratching their names into the lead of their belt buckles.

Private jewelry companies, including Drowne & Moore Jewelers, located in New York City, began to sell silver identity tags to soldiers who could afford them and family members would sometimes fashion makeshift tags from bits of lead, copper, or even old coins.

It was mobile tent stores operated by sutlers – itinerant, civilian merchants who followed the armies selling tobacco, coffee, sugar, and other goods directly to the soldiers, however, who perhaps produced the bulk of identity tags for soldiers in the field on the verge of battle.

Using a small machine that would stamp designs into metal discs made of brass or lead, the sutlers created the first “dog tags” used by soldiers fighting on American soil. Very few of these identification tags for Confederate soldiers have been found. The sutlers’ primary market were Union soldiers who typically possessed the resources to purchase such ID devices.

Sadly, even though many Union soldiers purchased, and presumably wore, the sutler’s dog tags, of the 325,230 federal soldiers who are buried in National cemeteries, 148,883 are marked unknown. It is estimated that 5% of the combined Civil War Union and Confederate dead remain unidentified.

The War Department eventually adopted identity tags, or “dog tags”, forty-four years after Secretary of War Edwin Stanton’s initial refusal to do so.