A Short History of the town of Broome

Much of the information included in this account was found in: Town of Broome 1797-1997 The First Two Hundred Years, written by Carol Buschynski with help and encouragement from Betty Chichester.

Edits and updates provided by Erika Eklund

Photos courtesy of Steve LaMont and NYGenWeb

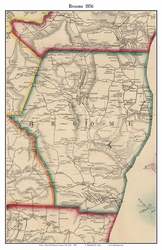

The town of Broome was established on March 17, 1797 as one of the six original towns formed in Schoharie County.

First known as Bristol, its name was changed to Broome on April 6, 1808 in honor of then Lieutenant Governor John Broome, who was much admired in this portion of the state for his sterling honesty, strict integrity and high political ability.

Broome lies on the east border of the county, south of the center. The surface is hilly upland, broken by deep ravines. The highest summits are from 350 to 500 feet above the valley. The Catskill Creek starts in the north part of the Vlaie in Franklinton and several branches of the Schoharie Creek drain the north and west portions.

Catskill Creek rises in the northern part of the town, flows southeastward, through Albany County and empties into the Hudson. Keyser’s Creek rises in the southern part of the town, flows northwest and empties into the Schoharie Creek at Breakabeen. Little Schoharie, also called Stony Creek, rises in the eastern part between branches of the Catskill Creek, flows northward through the town, then westward through Middleburgh, and empties into the Schoharie Creek opposite to Line Kill, the boundary between Middleburgh and Fulton.

Broome’s history is deeply intertwined with the neighboring towns of Conesville, Gilboa, and Middleburgh. The original town was very large and included over the half of the present towns of Gilboa and Conesville. The hub was Broome Center which is located in the present town of Gilboa. The first town meeting was held at the house of Peter Richtmyer located in the present day town of Conesville.

In 1836, a part of Broome was split off and combined with parts of Durham to form Conesville. In 1848, another split was made to form Gilboa. The town once again increased its size by annexing sections of Middleburgh in 1849.

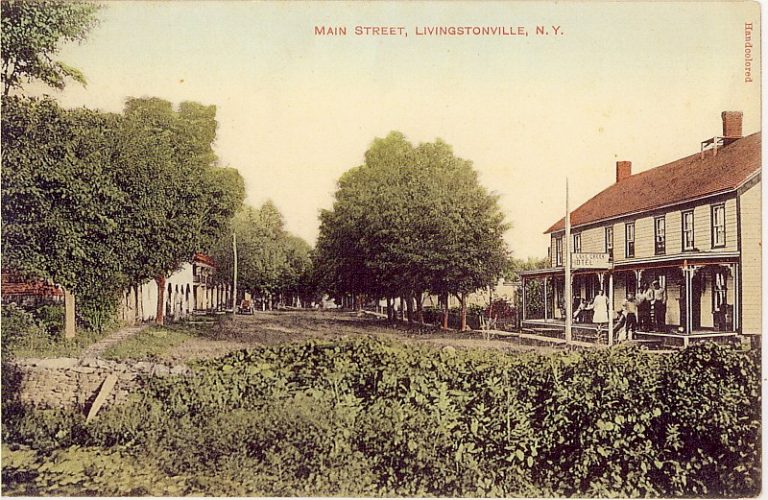

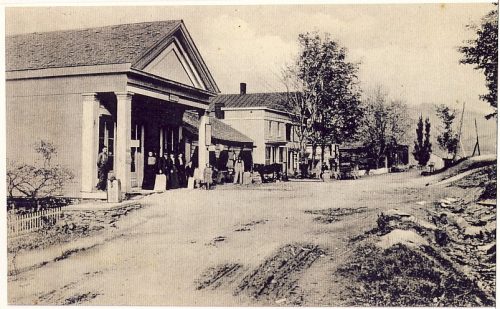

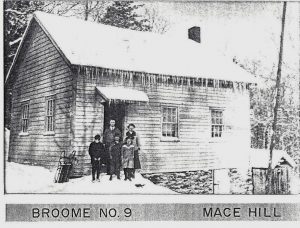

In 1860, Broome was a thriving community with a population of 2,182. Many farms dotted the hillsides and businesses abounded in the four major settlements of Livingstonville, Hauverville, Franklinton, and Bates (originally called Smithton).

The hamlet of Livingstonville had a hotel, two churches, two stores, a post office, school, shoe shop, two blacksmith shops, grist mill, sash and blind factory, as well as two doctors, a lawyer, and an undertaker.

Franklinton had a church, school, store, post office, wagon-making shop, grist mill and two blacksmith shops.

Bates had a church, school, sawmill, store, and blacksmith shop.

Hauverville had a church, school, store, blacksmith shop, cider mill, tannery, wagon shop, sawmill, and shingle factory. It also had a quarry which supplied stones for the Capitol building in Albany.

By 1980, the population of the town had declined to 761. Census figures for 2010 showed a slight reversal of that decline, showing a population of 973, up 2.7 percent over the previous 10 years.

Over the years, many old non-working farms were divided into parcels and sold for summer homes and hunting camps.

Vlaie Pond

Today, the town of Broome is probably best known for Vlaie Pond. Franklinton Vlaie (or Vly) is located along New York State Route 145. It is a unique scenic, recreational, and ecological wonder. This freshwater wetland is an invaluable resource for wildlife habitat, open space, and flood prevention. State stewardship insures the protection, preservation, and conservation of this resource for future generations.

Historical Residents of Note:

Daniel Shays – An American soldier, revolutionary, and farmer famous for being one of the leaders and namesake of Shays’ Rebellion, a populist uprising against controversial debt collection and tax policies in Massachusetts in 1786 and 1787 purchased a large tract of land near Preston Hollow (Cheese Hill) in 1791, much of which lay in the yet to be formed town of Broome.

While Town of Broome 1797-1997 The First Two Hundred Years indicates Shays passed away in Preston Hollow in 1821, recent research revealed he passed away four years later, in 1825, in the western New York town of Sparta.

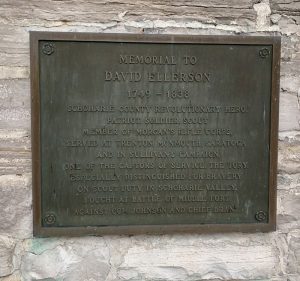

David Ellerson – A native of Virginia, David Ellerson became a Revolutionary War hero in Schoharie County, patriot soldier, scout and member of Morgan’s elite Rifle Corps. He settled in the town of Broome in 1793.

During his time in service, Ellerson served at Trenton, Monmouth, Saratoga, and in Sullivan’s Campaign. He is especially distinguished locally for his bravery and scout duty performed in the Schoharie Valley and for fighting at the Battle of Middle Fort.

Ellerson passed away in the town of Gilboa on August 24, 1839 at the age of 89. He was laid to rest at the Flat Creek Cemetery in Gilboa.

David Williams – David Williams was born in Terrytown on October 21, 1754. He was a farm laborer until the age of 21, when he entered the Army and served as a New York militiaman during the American Revolution.

Local legend has it that the David Williams Farm, on Cheese Hill in the town of Broome, was built by Williams in 1806 with prize money he received from aiding in the capture of Major John Andre, a British spy, who was hanged because of his involvement with General Benedict Arnold for the surrender of West Point. The property was previously owned by Daniel Shays, of Shay’s Rebellion.

In the year before his death, the fall of 1830, New York City invited him to a celebration of the French Revolution, sent a special escort for him, made much of him, and at the time he was given a silver cup and a silver headed cane. Both items can be found along with several other of Williams’ possessions in the first floor gallery at the Old Stone Fort Museum.

David Williams died on August 2, 1831 at the age of 77. He was buried with military honors in the Livingstoneville Cemetery. His remains were moved to Rensselaerville on March 4, 1876 and on July 19, 1877, his remains were again moved to the Old Stone Fort in Schoharie where they still remain.

On September 23, 1876, the largest crowd ever assembled in Schoharie at the time – some 10,000 people – witnessed the dedication of the David Williams monument, just outside the big wooden door of the Old Stone Fort.

You can visit the monument of the “incorruptible patriot” David Williams at the Old Stone Fort still today.